She stresses how, as a political culture as much as anything, white evangelicalism captivated believers enough to redraw the boundaries of faith around political allegiance rather than creedal assent. She shows how militant white Christian patriarchy paved the way for a fractured nation and a ruined religion whose doctrine of grace and commandment to love diminish in the face of political expedience.

Without it, America would allegedly go the way of wusses, weakening as a nation into a soft and too-delicate democracy.ĭu Mez saddles up with Teddy Roosevelt as a Rough Rider and giddyups all the way to the present, lassoing the likes of Billy Sunday and Billy Graham, Jerry Falwell and James Dobson, Duck Dynasty and Mark Driscoll, along with plenty of other Christian cowboys (and a few cowgirls too). Masculine power was essential to America fulfilling its calling. With the evangelical embrace of morals legislation came a commitment to order and hierarchical authority, starting at the top with God and manifested in strong male leadership in government, business, the military, churches, and families. And safeguarding that morality required various forms of government action. In the eyes of many Christians, America’s chosenness was linked with its morality, specifically in the areas of sexual ethics, family values, character education, freedom of (Christian) worship, and a potent foreign policy.

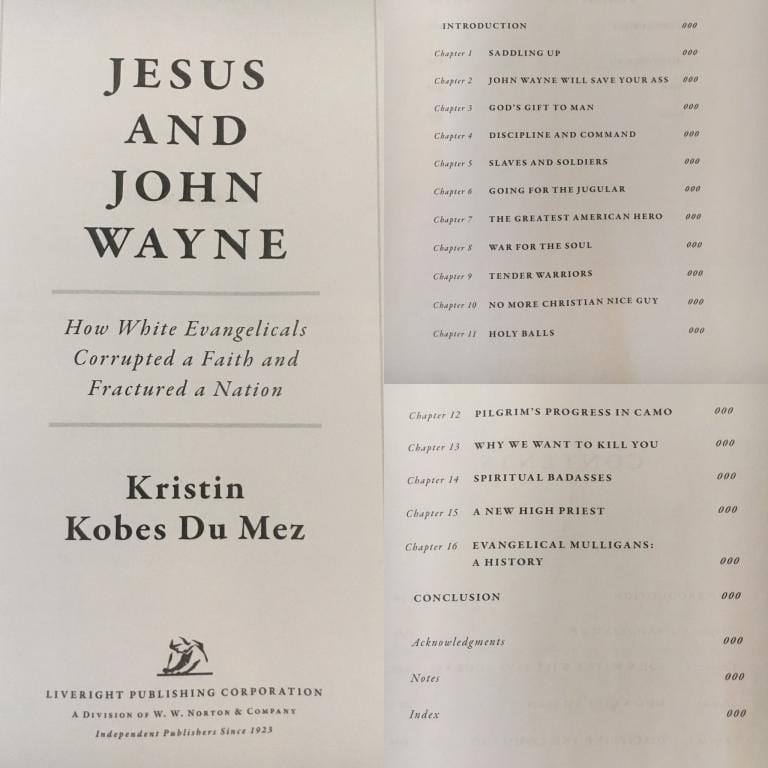

Invoked by successor presidents Clinton, Bush, and Obama, the notion of American exceptionalism became core to the national identity. The popular idea of America as God’s chosen nation traces back to Puritan leader John Winthrop’s 1630 “city on a hill” sermon, which went mainly unnoticed (except by historians) until Ronald Reagan rolled it out amid the latter days of the Cold War. Effeminate features of Victorian piety would no longer do for a nation aspiring to righteous superpower. A ‘Masculinity Problem’Įarly in the 20th century, Du Mez writes, “Christians recognized that they had a masculinity problem.” If America was to be truly great and fully Christian, it had to man up. As it turned out, Du Mez argues, obedience wasn’t as much about goodness and grace as it was about power and who wielded it. In her recent book, Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, Calvin University historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez situates Gothard and Piper in a long line of white, alpha-male leaders whose devotion to a militant Christian patriarchy and nationalism inevitably led to exuberant support, among large numbers of white evangelicals, for Donald Trump as president-despite his clear deviation from anything evangelical in a spiritual or behavioral sense. The place was packed, mostly with young, male, goateed enthusiasts, wide-eyed in wonder over how good they had it as men in God’s economy. The Lord established male headship over women as part of creation’s order, Piper taught, for his glory and our joy. We hosted a special event featuring the popular Reformed evangelical pastor John Piper, who like Gothard stressed the importance of obedience in a hierarchical chain of command starting with God and descending to men over women and children. It was how authority in the universe supposedly worked.įast forward 20 years to a congregation I served as a minister in Boston. Moreover, God structured things such that she actually had to forgive me since she was a woman and I was a man. I told her about the seminar, about obedience and the blessings that awaited us both if she’d obey and forgive me. Needless to say, she was nonplussed and wondered why in the world I was calling. Gothard offered a script of contrition, so I looked up her phone number, dialed, and read my repentance. My mind immediately went to a high-school girlfriend I’d heartlessly dumped as I made my way to college four years prior.

To be released from former transgressions freed us for future treasure, or something like that. Past conflict clogged up one’s conscience. Specifically, Gothard directed us to seek out those we’d offended and ask forgiveness. Obedience begets blessings, peace of mind, and confidence in one’s relationship with God. Gothard’s principles for life’s dilemmas included specific practices based on the Bible. Authority is God-given, Bill Gothard taught, and in his moral universe, any diversion from obedience disturbed the force and ignited interpersonal conflict, along with personal anger and resentment.

As a recent college graduate in 1983, I sat spellbound with thousands in my southern city civic center, mesmerized by a mousy man projected on a big screen who taught us we must submit to authority in every domain of life.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)